- 1. The Secret Power of ‘Read It Later’ Apps

The Secret Power of ‘Read It Later’ Apps

#Omnivore

Read on Omnivore

Read Original

Image via Nuno Cruz

By Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

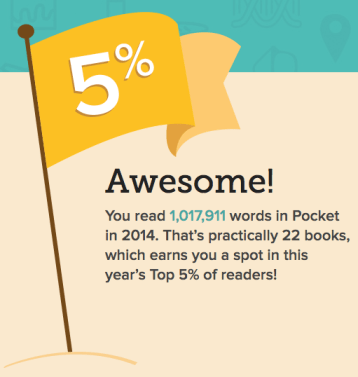

At the end of 2014 I received an email informing me that I had read over a million words in the ‘read it later’ app Pocket over the course of the year.

This number by itself isn’t impressive, considering our daily intake of information is equivalent to 34 gigabytes, 100,000 words, or 174 newspapers, depending on who you ask.

What makes this number significant (in my view) is that it represents 22 books’-worth of long-form reading that would not have happened without a system in place.

We’ve made a habit of filling those hundred random spaces in our day with glances at Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. But those glances have slowly become stares, and those stares have grown to encompass a major portion of our waking hours.

The end result is the same person who spends 127 hours per year on Instagram (the global average) complains that she has “no time” for reading.

The fact is, the ability to read is becoming a source of competitive advantage in the world.

I’m not talking about basic literacy. What has become exceedingly scarce (and therefore, valuable) is the physical, emotional, attentional, and mental capability to sit quietly and direct focused attention for sustained periods of time.

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review puts a name to this new neurological phenomenon: Attention Deficit Trait. Basically, the terms ADD and ADHD are falling out of use because effectively the entire population fits the diagnostic criteria. It’s not a condition anymore, it’s a trait — the inherent and unavoidable experience of modern life characterized by “distractibility, inner frenzy, and impatience.”

Start Building Your Second Brain

Subscribe below to learn more about the next cohort of the Building a Second Brain course

Read It. Later.

Before I explain the massive, under-appreciated benefits these apps provide, and how to use them most effectively, a quick primer in case you’re unfamiliar.

So-called “Read It Later” apps give you the ability to “save” content on the web for later consumption. They are essentially advanced bookmarking apps, pulling in the content from a page to be read or viewed in a cleaner, simpler visual layout.

On top of that core function they add features like favoriting, tags, search, cross-platform syncing, recommended content, offline viewing, and archiving. The most popular options are:

- Instapaper

- Send to Kindle (for sending articles to your Kindle)

- Feedly (for those RSS fans)

- and Safari’s built-in “Add to Reading List” feature.

The app I use, Pocket, adds a button to the Chrome toolbar that looks like this:

Chrome toolbar

Note: at time of writing, I was using Pocket, but have recently switched to Instapaper because of Pocket’s “Share to Evernote” bug mentioned below.

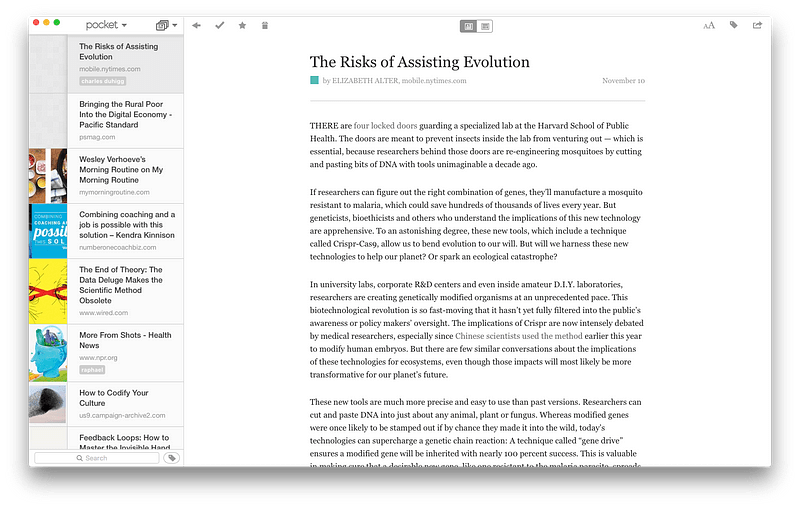

Clicking the button while viewing a webpage turns the button pink, and saves the page to your “list.” Navigating to getpocket.com, or opening the Pocket app on your computer or mobile device shows you a list of everything you’ve saved:

Mac desktop client

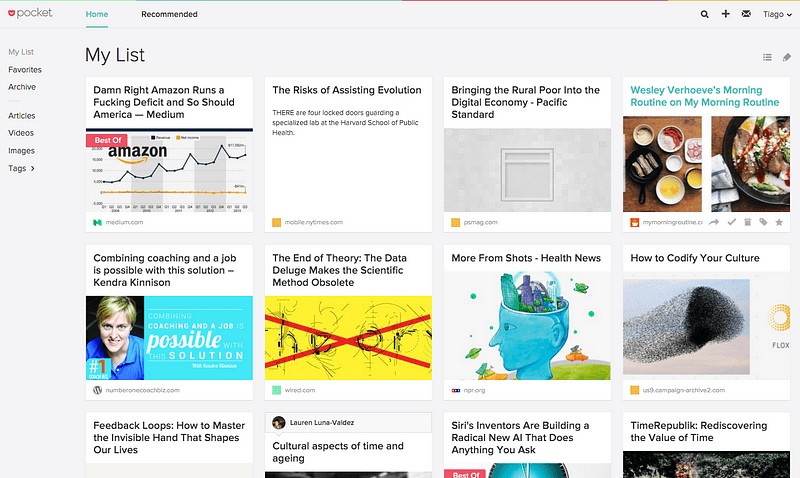

You can also view your list in a “tile” layout on the web, making it into essentially a personalized magazine. Personalized, in this case, not by a cold, unfeeling algorithm, but by your past self:

Web browser “tile” view

Marking an item as read in one version of the app will quickly sync across all platforms. It will also save your current progress on one device, so you can continue where you left off on a different device (for those longer pieces).

The highest leverage point in a system is in the intake — the initial assumptions and paradigms that inform its development

I’ve written previously about how to use Evernote as a general reference filing system, not only to stay organized but to inspire creativity.

But I didn’t address a key question when creating any workflow: how and from where does information enter the system? The quality of a workflow’s outputs is fundamentally limited by the quality of its inputs. Garbage in, garbage out.

There are A LOT of ways we could talk about to improve the quality of the information you consume. But I want to focus now on the two that Read It Later apps can help with:

- Increasing consumption of long-form content (which is presumably more substantive)

- Better filtering

#1 | Increasing Consumption of Long-Form Content

In order to consume good ideas, first you have to consume many ideas.

This is the fundamental flaw in the “information diet” advice from Tim Ferriss and others: strong filters work best on a larger initial flow. Using your friends as your primary filter for new ideas ensures you remain the dumbest person in the room, and contribute nothing to the conversation.

The problem is that our entire digital world is geared toward snackable chunks of low-grade information — photos, tweets, statuses, snaps, feeds, cards, etc. To fight the tide you have to redesign your environment — you have to create affordances.

Affordance (n.): a relation between an object and an organism that, through a collection of stimuli, affords the opportunity for that organism to perform an action.

Let’s look at the 4 main barriers to consuming long-form content, and the affordances that Read It Later apps use to overcome them:

1. App performance

We know that the most infinitesimal delays in the loading time of a webpage will dramatically impact how many people stay on the page. Google found that increasing the number of results per page from 10 to 30 took only half a second longer, but caused 20% of people to drop off.

If you think your behavior is not affected by such trivialities, think again. Even on a subconscious level, you will resist even opening apps that don’t reward you with snappy response times. Which is a problem because the apps most people turn to for reading are either ebook apps like iBooks and Kindle, or web browsers like Chrome and Safari. I’m not sure which category is slower, but they’re both abysmal.

Meanwhile, your snaps and instas refresh at precog-like speeds.

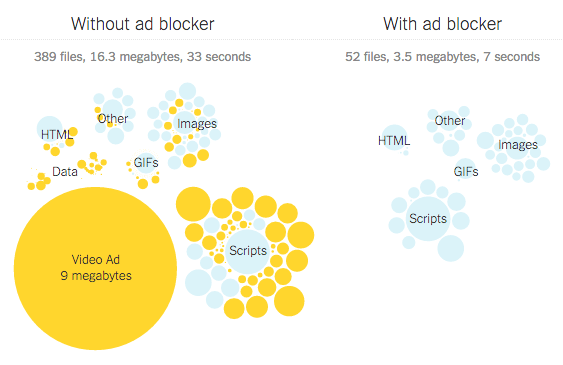

Read It Later apps, by slurping in content (articles, videos, slideshows) into a clean interface, eliminate the culprits — ads, site analytics, popups — all the stuff you don’t care about.

A recent analysis by The New York Times of 3 leading ad-blockers (which have the same effect) measured a 21% increase in battery life, and in the most egregious case of Boston.com, a drop in loading time from 33 seconds to 7 seconds. Many other leading sites were not that far off.

Effect of ad-blocker on loading times of Boston.com, via NYT

Yeah that’s pretty much an eternity in mobile behavior land.

2. Matching content with your context

My Pocket list on iPad

Much of the time when we pull out our phone, we’re looking for something to match our mood (or energy, or time available, or other context). We use our constellation of shiny apps as mood regulators and self-soothers, as time-fillers and boredom-suppressors, for better or worse.

So you need a little entertainment, and you open…an ebook? Yeah right. Monochrome pages don’t attract you. They don’t draw you in.

Pocket gives reading some of this stimulatory pleasure by laying out your list in a pleasing, magazine-style layout (at left). Not only is it generally attractive, but it gives you that same magazine-flipping pleasure of engaging with something that interests you right in that moment.

David Allen puts it this way:

“It’s practical to have organized reading material at hand when you’re on your way to a meeting that may be starting late, a seminar that may have a window of time when nothing is going on, a dentist appointment that may keep you waiting, or, of course, if you’re going to have some time on a train or plane. Those are all great opportunities to browse and work through that kind of reading. People who don’t have their Read/Review material organized can waste a lot of time, since life is full of weird little windows when it could be used.”

You’re not fighting your impulses forcing yourself to read a dense tome after a long work day. Willpower preserved ✓

3. Asynchronous reading

This is one of the least understood barriers to reading in our fragmented timescape.

There is something deeply, deeply unsatisfying about repeatedly starting something and not finishing it. This is what we experience all day at work, being continuously interrupted by a stream of “emergencies.” The last thing we want after a stressful day starved of wins is to fail even at reading an article.

The 2015 revised edition (affiliate link) of Getting Things Done cites the work of Dr. Roy Baumeister, who has shown that “uncompleted tasks take up room in the mind, which then limits clarity and focus.” The risk of cognitive dissonance at not being able to finish a long article (much less a book) keep us from even beginning it.

Read It Later apps address this by simply saving your progress in a given article, allowing you to pick back up at a different time, or on a different device, and clearly marking items as “read” once you’re finished.

4. Focus

A common response when I recommend people adopt yet another category of apps is “Why don’t I just use Evernote?” Or whatever app they’re using for general reference or task management. Evernote even makes a Chrome extension called Clearly for reading online content and Web Clipper for saving it.

It is a question of focus. Why don’t you use your task manager to keep track of content (i.e. “Read this article”)? Because the last thing you want to see when you cuddle up with your hot cocoa for some light reading is the hundreds of tasks you’re not doing.

Likewise, the last thing you want to see when you (finally!) have time to read is the thousands of notes you’ve collected from every corner of the universe, only some of which you haven’t read, only some of which you want to read, only some of which are meant to be read.

Actionable info ≠ Reference info ≠ To Read pile

Ergo,

Task manager ≠ Evernote ≠ Pocket

#2 | Better filtering

Now you’ve got the funnel filled. It’s time to narrow it.

Most advice on this topic focuses on being more selective about your sources. Cutting out the email digests that just throw you off track, unfollowing people posting crap, or even directly replacing ads with quality sources.

The problem is that this assumes you are always at your best, always at 100% self-discipline, totally aligned with your life values, priorities ship shape.

Yeah.

In the moment, with your blood sugar at a negative value and every fiber of your being screaming for a dopamine hit, of course that Buzzfeed article seems like the best conceivable use of your time. If you think you can permanently seal off your life from the celebrity news, content marketing, and spammy friends that dominate the web, the NSA has a job for you.

Procrastination is the most powerful force in the universe. It will find a way.

I have a different approach: waiting periods. Every time I come across something I may want to read/watch, I’m totally allowed to. No limits! The only requirement is I have to save it to Pocket, and then choose to consume it at a later time.

I’ve found that even just clicking a link to open the URL, in order to save it to Pocket, is too much of a temptation. The first glimpse of a cute GIF and I’m off to Reddit, completely forgetting my morning email session.

So instead I just command-click every link I’m interested in (or right-click > Open link in new tab), which opens each link in a separate tab without taking me to that tab.

Here’s what a typical Monday morning link-fest looks like, just from email:

Then, because I’m still in collection mode, not in read mode, I cycle through each tab one at a time (shift-command-} or control-tab), saving each one to Pocket using the shortcut I set up: command-p (chosen for irony and to avoid inadvertent printing).

There’s only one rule: NO READING OR WATCHING!

Bringing this back to filtering, not only am I saving time and preserving focus by batch processing both the collection and the consumption of new content, I’m time-shifting the curation process to a time better suited for reading, and (most critically) removed from the temptations, stresses, and biopsychosocial hooks that first lured me in.

I am always amazed by what happens: no matter how stringent I was in the original collecting, no matter how certain I was that this thing was worthwhile, I regularly eliminate 1/3 of my list before reading. The post that looked SO INTERESTING when compared to that one task I’d been procrastinating on, in retrospect isn’t even something I care about.

What I’m essentially doing is creating a buffer. Instead of pushing a new piece of info through from intake to processing to consumption without any scrutiny, I’m creating a pool of options drawn from a longer time period, which allows me to make decisions from a higher perspective, where those decisions are much better aligned with what truly matters to me.

Remove any feature, process, or effort that does not directly contribute to the learning you seek. — Eric Ries, The Leader’s Guide

Here’s a visual of how this works, from my Pocket analytics:

You can see that I save more things toward the beginning of the week and the weekend, and then draw down the buffer more towards the end of the week.

/sidebar

Imagine for a second if we could do this with everything. On Saturday morning, well-rested and wise, you retroactively decide everything you want to have done during the previous week. Anything you decide was not worthwhile, you get that time back.

I experienced this recently with email — after returning from a 10-day meditation course during which I was completely off the grid, I was surprised to notice it took only 1.9 hours to process almost 2 weeks’ worth of email (I track these things). I normally spend on average 2.19 hours on email per week — what happened to those extra 2.48 hours?! Besides the gains from batch processing such a large quantity of emails at once, I believe the main factor was that I evaluated my emails from a longer time horizon and higher perspective, more correctly judging whether something was worth responding to or acting on.

If only this method would scale.

/end_sidebar

Mo’ apps, mo’ problems

There are drawbacks, which I’ve glossed over until now. The two main ones:

1. Formatting issues

Many sites, including popular ones, aren’t presented correctly within the Pocket app (and I imagine others). There’s always the option of opening the link in a web browser, but this eliminates all the positive affordances and then some. If there wasn’t so much value provided otherwise, this would be a deal breaker.

The worst part is that, sometimes, the article is cut off or links don’t appear without any indication that something is amiss. On Tim Ferriss’ blog, for example, links (of which there are many) are simply removed.

One solution is to tag problematic items with “desktop” so you know that these need to be read/viewed on your computer.

2. Dependence

Every productivity tool eventually becomes a victim of its own success. In this case, I’ve become so dependent on Pocket that bugs really affect me.

For example, the Share to Evernote feature, which I use to highlight and save key passages, has been broken for at least a month. My hysterical tweets to Pocket Support have been answered but not resolved.

You wouldn’t think such a minor feature within one app could be so disruptive, but it has been massively so. This simple workflow:

Highlight > Share > Share to Evernote > Save

…has been replaced with this:

Highlight > Copy > Switch to Evernote > New note > Paste > Switch back to Pocket > Share > More > Copy URL > Switch back to Evernote > Paste URL > Switch back to Pocket

Worse, I often forget to go back and grab the URL, so I have to hunt it down at some later date.

/rant_over

Progress Traps and Paradigms

The amount of information in the world is a progress trap. Too much stuff to read is just as limiting as too little.

As the inimitable Venkatesh Rao has written, we’re moving from a world of containers (companies, departments, semesters, packages, silos) to a world of streams (social networks, info feeds, main streets of thriving cities, Twitter). Problems and opportunities alike resist having neat little boxes drawn around them. There’s way too much to absorb. Way too much to even guess what you don’t know.

As the pace of change in the world accelerates, we double down on all the methods that created the problems in the first place — more planning, more forecasting, more control and risk management. We’re left with massive institutions that nobody trusts, that are simultaneously brittle and too-big-to-fail, creating precarity at every level of the socioeconomic pyramid.

What would it look like instead to solve problems (and explore opportunities) in a way that gets better the faster we go?

I can’t do justice to Rao’s blog series linked above (it’s in 20 parts — may want to save it for later 😉, but the first step he proposes is “exposing yourself to as many different diverse streams as possible.”

When you’re immersed in a stream, the faster it goes, the more novel perspectives and ideas you’re exposed to. You develop an opposable mind — the ability to juggle and play around with different perspectives on any issue, instead of seeing it through one lens.

Increasingly, the only metric that will matter in your journey of personal growth will be ROL: Rate-of-Learning. We’ve heard a lot in recent years about the importance of hands-on learning and practical experimentation. We get it. Burying your head in a book by itself gets you nowhere.

But the pendulum is swinging too far in that direction. Yes, you can be too action-oriented. Ideas, while cheap when compared to effective execution, are still more valuable than many of the other things we spend time on.

There’s another way to learn faster: assimilate and build on the ideas of others. Sure, you won’t understand every tacit lesson their experience gave them, but you can incorporate many of them, and in a fraction of the time it would take you to make every mistake yourself.

Ideas are high leverage agents. They become more so when arranged in highly cross-referenced networks. The only tool we have available that is capable of both creating and accessing these networks on demand is the human brain.

I lied before. There is one form of leverage even more powerful than the initial assumptions and paradigms that inform a system’s development: the ability to transcend paradigms.

I can’t put it any better than Donella Meadows, in her seminal piece on complex systems:

People who cling to paradigms (which means just about all of us) take one look at the spacious possibility that everything they think is guaranteed to be nonsense and pedal rapidly in the opposite direction. Surely there is no power, no control, no understanding, not even a reason for being, much less acting, in the notion or experience that there is no certainty in any worldview. But, in fact, everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment. If no paradigm is right, you can choose whatever one will help to achieve your purpose.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that people throw off addictions, live in constant joy, bring down empires, get locked up or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.

In the end, it seems that mastery has less to do with pushing leverage points than it does with strategically, profoundly, madly letting go.

Reading is the closest thing we have to thinking another’s thoughts. It’s long and sometimes ponderous, but that work is required to wrap yourself in another person’s paradigm. Which is the first step in madly letting go of your own.

The amazing thing about ideas is that it takes zero time for one to change your paradigm. It happens in time, but takes no time, like an inter-dimensional wormhole, one entangled particle in your brain mirroring its twin across a chasm even more vast than the universe — the chasm between two minds.

And that is the secret power of Read It Later apps.

P.S. My latest setup has 2 parts: 1) using this IFTTT recipe to automatically send “liked” articles in Instapaper to an Evernotebook called “Instapaper favorites” (for things I want to save in general but don’t have any particular notes on), and 2) this recipe that saves anything I highlight in Instapaper to a new note, and sends it to the Evernote default notebook where I can decide where it belongs later (for when I have specific passages I want to extract)

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

Join the Forte Labs Newsletter

Join 50,000+ people receiving my best ideas on learning, productivity & knowledge management every Tuesday. I’ll send you my Top 10 All-Time Articles right away as a thank you.

- POSTED IN: Building a Second Brain, Curation, Free, Note-taking, Technology, Workflow